“ I can’t love you how you want me to / Here’s the best part, distilled for you /

But you want what I can’t give to you / Your hands are gravity while my hands are tied… ”

— Bite the Hand, Boygenius

“ Where you go I will go, and where you stay I will stay.

Your people will be my people and your God my God. ”

— Ruth 1:16-17

It’s going to rain soon, and Kathleen is in love with the weatherman.

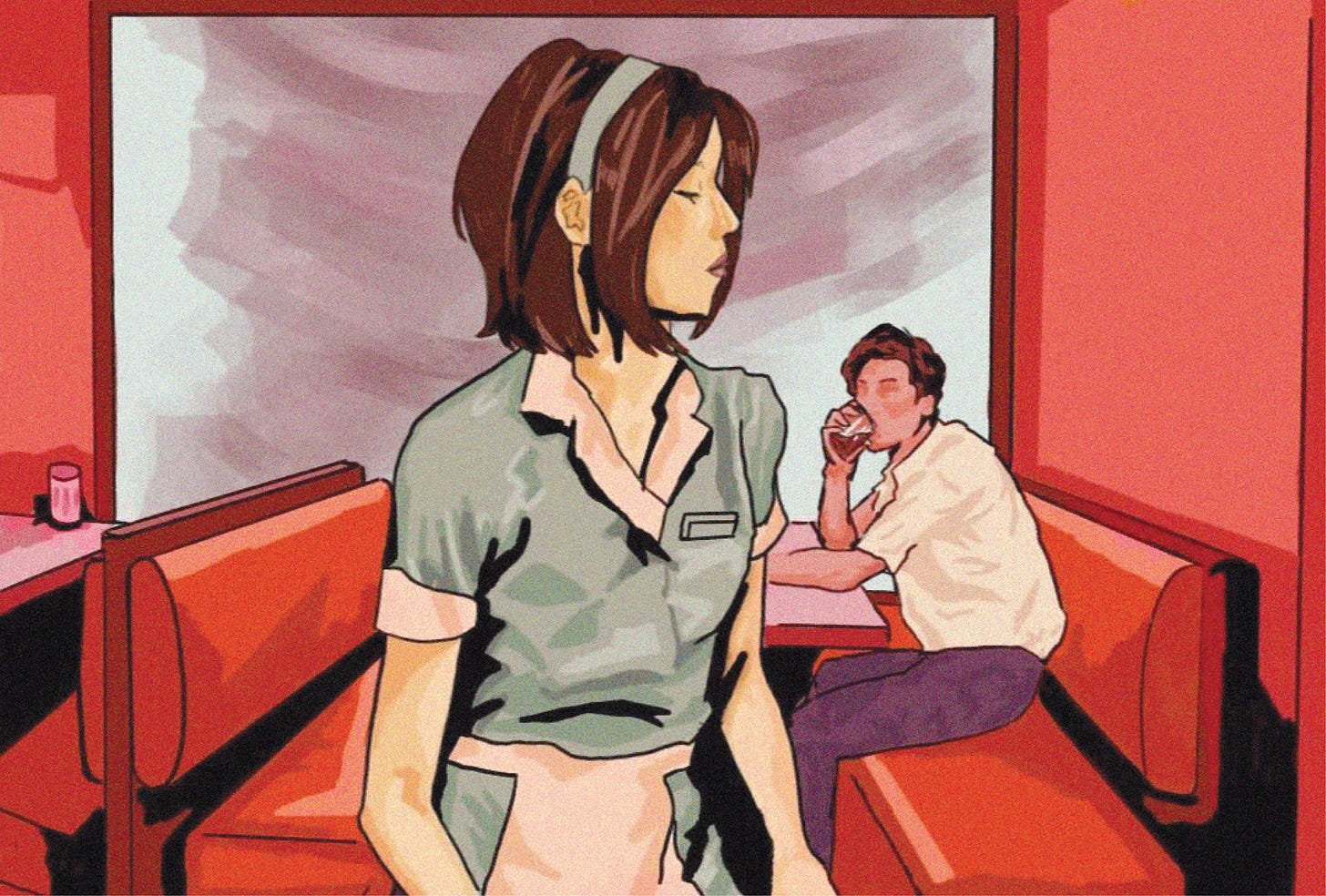

It’s a slow day at the diner, the rain coming down hard in grey sheets, and Kathleen’s feet are killing her. The vintage tan saddle shoes are part of the uniform, the owner says they contribute to the ambience of the establishment. Kathleen thinks they’re a carefully curated torture device designed to keep the waitstaff and kitchen staff from unionizing. You aren’t at risk of walking out if you’ve been on your feet from nine to five, six days a week, every week for the last two years. Can’t march with blisters like stigmata burning through your feet.

The windows rattle as the storm pulsates outside, wind beating against the side of the diner relentlessly. Earlier that morning, when Kathleen had first opened, the whole building had shaken so bad she’d dropped a carton of eggs on its head. Yolk is a surprisingly difficult thing to scrub out of linoleum flooring, her saddle shoes were still sticky.

On the little TV mounted to the wall across from the counter, the weather report plays at minimal volume. Raine Turner is standing outside the Parrish cornfield wearing a bright orange raincoat and looking into the camera with his signature smolder. His voice somehow manages to boom over the torrential downpour, cutting clean through Kathleen’s skin and burrowing somewhere in her stomach. Raine begins his run-through of what to expect as the storm progresses, his white teeth flashing stark against the bruising background.

Raine Turner first started doing the weather when Kathleen was in middle school. She’s only missed two of his reports since. She used to want to be a meteorologist because of him and, in her wildest dreams, a storm chaser like Helen Hunt in that movie from the 90’s. A part of her still wants this, craves the salt of a storm. But it’s the kind of want that’s conflicting at best, silly at worst.

It’s hard to articulate exactly why she’s in love with him. He’s handsome, of course, but that’s the last thing Kathleen is inclined to love about him. Since the very first time she saw him on TV, she’s been jealous of him. Of the way he carries himself, of his confidence and his grace, the effortless charm and ease with which he delivers their county the daily weather reports. Mostly, though, Kathleen’s jealous of how much he obviously loves his job. She’s never known what it’s like to have so much love for something, to come alive under the knowledge of interest. On the TV, Raine Turner is gesticulating wildly as the wind picks up around him. Whoever’s holding the camera is shaking so bad that Raine’s face is pixelated and distorted by weather. It’s been a while since they had a serious tornado. The ones last season were little events, just miniscule dustups that left everyone with mild allergies and migraines. Raine hasn’t outright said anything about a tornado yet, though. It’s likely the kind that just happens sometimes when it rains this hard for this long, but Kathleen knows.

When you live your whole in a place where wind can kill you faster than old age, you develop a sixth sense. Kathleen’s oldest friend used to say that she had the spine of a storm, a wayward soul that moved as it pleased, and a body meant for staying put. Gravity pulling at her core so viciously a blackhole had opened next to her littlest vertebra right around the time she first got her period in ninth grade.

Kathleen experienced her first tornado when she was only a few hours old. It was her mother’s favorite story to tell. Taurus season, 2002. There’d been a freak outbreak of tornadoes across the Midwest and coal country. Five hours postpartum, sore, and bleeding; her mom had sat in a dusty hospital basement with twenty other patients, doctors, nurses, and baby Kathleen bundled up in her arms. Apparently, Kathleen never made a peep. She’d always been a good girl, according to her mother.

Growing up in tornado alley, cow shit, and Jesus Kansas, Kathleen thinks she probably just had a preternatural interest in tornadoes, even then. They could take away so easily, so quickly, and the idea of anything possessing that kind of power has always made Kathleen giddy. Even still, she won’t let the reality of a tornado set in until Raine gives the warning. She could never.

Kathleen remains entirely focused on Raine as the front door bangs open, the bell violently swinging side-to-side. Kathleen doesn’t have to look to know that Ruth Sadecki is standing in the doorway as if Kathleen conjured her herself. Ruthie is like a personified second-coming, both personally and regarding Kathleen’s fraught existence. She wishes Ruth would’ve drowned on her walk here. That would have made her life so much easier.

“Kathy!”

Kathleen cringes. They’ve been Ruthie and Kathy since they were thirteen, the only two girls in their grade at St. Mary’s to have gotten scholarships. Everyone thought of them as extensions of the other, attached at the hip and girlishly infallible. Kathleen saw it as two adolescent girls ignoring the blood spilling from their mouths whenever they touched.

If Kathleen has the spine of a storm, Ruth has the body of benefaction. She’s soft where Kathleen is sharp. Ruth is all supple, daring and ruthless in her caring. Kathleen could never quite figure out how to let Ruth exist around her, near her, in her life without wanting to tame parts of her that demanded a gentleness that Kathleen was born without.

Ruth is talking. Ruth is always talking. Kathleen is always forgetting to pay attention. Flinging off her jacket and sitting directly across from her, Ruth’s gaze is hot against Kathleen’s uniformed back, appraising every inch of her, scorching and observant. Something in her flips and curls, nausea riding up her throat.

Kathleen kind of wants to slap her, just a little. Just to see what would happen. If Ruth would recoil, she’d press a shaking palm to her cheek and look at Kathleen with pure hatred. If she would leave— not just the diner but Kathleen — she would remove herself entirely and leave Kathleen to yearn in peace. Maybe she’d reach over the counter and hit her back, slap her so hard she’d fall against the wall, breaking dishes with the sheer force of her body. Ruth could make Kathleen bleed, if she wanted to. And Kathleen could make Ruth bleed, make Ruth hate her, make her irrelevant. If she wanted to.

They were born in a place that could so easily be taken apart by disaster, a place that most people find it hard to imagine anyone existing in, much less growing up and living and surviving. It’s easier for Kathleen to find comfort in chaos than anything else.

The thing about working at the diner is that it’s like working in a fishbowl. No privacy, not even in the kitchen. The customers can hear a great deal, see most things, and judge everything. It’s being on display 24/7, serving up your competency on a silver platter and stripping the metal when you’re having a bad day. All of the parts of you distilled for other people’s finite pleasure. It makes Kathleen sick. She can still feel Ruth’s stare, her skin pricking at every place that Ruth’s eyes land.

Kathleen lets her eyes go in and out of focus as a commercial drones on, waiting impatiently with her heart in her stomach for Raine’s program to return. She thinks a lot. Really, she’s always thinking. And right now, Kathleen can’t stop imagining a tornado tearing through the old Parrish cornfield before anyone has the chance to evacuate. Right now, Kathleen’s imagining the tornado squaring up to Raine Turner and ripping him limb from limb, flinging the rest of his body through a solid brick wall. Right now, she really can’t deal with the hot knife of Ruth’s attention raking across her skin and leaving behind blistering, melted skin.

Outside, lightning is followed by a loud clap of thunder, accentuated by the lonely insides of the diner. Kathleen doesn’t even flinch.

“There’s going to be a tornado,” Ruth states bluntly. She doesn’t sound like this is a revelation recently made. No, Ruth says this as though it’s a fact. A thing she’s known this whole time, even before entering the diner and interrupting Kathleen’s alone-time with the weather report.

“You don’t know that. Not for sure. Not until Raine reports it,” Kathleen snaps, her eyes glued to the television and her hands tightly grasping each other across her chest, fingers worrying at the empty space above her breastbone. Searching.

She’s the only one that showed up for work today. The only one who didn’t stay home because of the weather. Everyone said there was going to be a tornado, but their boss still had four people on the schedule. So, Kathleen showed up. Besides, even if the air hangs thin and oppressive, even if she knows — There’s no tornado until Raine says there’s a tornado.

“Do you remember when the parent-teacher board threw that big fundraiser to create a student news program? And they had those prayer candles made with Raine’s face printed across them like Jesus or Mother Mary, but they spelt his name wrong. Saint Rain, he worked so hard for this community that he was immortalized in a blasphemous mistake.” Ruth’s voice takes on a dramatic lilt, like she’s fifteen again, reciting Shakespeare in the school play. Her eyes rove across Kathleen’s body yet again, her hands shake at the attention. “You know whenever you talk about him, you sound exactly the same way my mom does when she talks about the book of Matthew.”

“You never talk about anything like that, you know.”

They were born in a place that could so easily be taken apart by disaster, and Ruth had the nerve to just sit there, staring at Kathleen with her ridiculous eyes, always at the brink of spilling over, and poke at her and poke at her and poke at her.

“That was mean, and you know it, Kathleen.”

Her fingers twitch. Outside, lightning cracks open the sky, and the rain pours down harder, beating the earth helpless.

Kathleen can’t do this right now. Can’t have a useless fight with a person who refuses to bite back, with a person who refuses to draw blood. Not when right now... Right now, Raine’s weather report has him in immediate danger. It’s undeniable, a tornado’s coming. It’s the beginning of the season, the time between birth and slaughter. Something tragic is due to happen soon. A tornado’s coming, and the one person that offers her any sort of escape is out in the middle of nowhere, waiting for it to come.

Kathleen can hear herself squeak and grunt, shoving off from the counter and hurrying into the empty kitchen —devoid of the weekend cook who failed to turn up earlier that morning— runs through the back hallway, and out the big heavy metal door leading behind the diner.

It’s like walking face-first into a storm cloud. Rain assaults her immediately, drenching her in seconds and filling her open mouth. She holds out her arms, tips her head up up up and lets water fill her nose, her mouth, her eyes, until there’s nothing left but rainwater tainted with ozone. Baptism, benefacted and true. A sick kind of blessing.

When she was younger, Kathleen had craved a body. Her god had thick hips and soft ankles, small tits, and a mouth sharp and glinting. But she’d also dreamt of something else. What the something else was, she still can’t name. She wrote in her diaries about floating outside of her body at night, or early in the morning at school. Watching herself, watching things happen to her instead of interacting with them. She used to think that if she had the ability to float even further outside of her body, move through ceiling after floor after ceiling and drift off toward something else, soft clouds and a place with trees as tall as business buildings, then maybe she could be gifted a presence. She could move in silence, unwatched and speechless.

Kathleen hasn’t even realized that she’s begun to wander away from the diner, out into the back parking lot. She is looking up at the sky, at the dark, complicated bruise of weather above her. If she could conjure lightning, she would.

She’s worried about Raine, of course she’s worrying about Raine, but once again she’s mostly jealous of him. How relieving it would be to be caught up in something as powerful and godly as a tornado. To be captured and chased from your body.

“Kathy! Kathy!” Ruth is screaming, hesitating before bolting after Kathleen and wrapping soft arms around her, dragging her back under the awning and refusing to let go.

“What were you doing?” Ruth’s voice sounds like tears, quiet and unbidden. Kathleen thinks maybe she can feel Ruth’s heartbeat against her back, sharp and erratic. Kathleen thinks a lot of things, but her mouth doesn’t work anymore. It’s too full.

“We have to go; your weatherman issued a tornado warning. There’ll be an alarm soon. Can we go to your cellar?” Her mouth is too full. “Kathy, we have to go! The alarm’s gonna sound any minute.” Ruth’s shaking her now, turning her around so she can look Kathleen in the eye.

Whatever she sees must be new, something she’s never seen in Kathleen before in all their years of friendship. Kathleen can’t even begin to fathom what. Ruth’s dimpled chin trembles, and she whispers so quietly the rain steals it, “Kathleen.”

There’s a tornado and the first thing Kathleen thinks about when she comes back to her body isn’t that they’re going to die; it’s Raine Turner. It’s Raine Turner standing in front of Parrish’s cornfield, in immediate danger of being swept away. It’s Raine Turner getting caught up, being separated from his body, and being made a spectacle of. It’s Raine Turner, dying alone. It’s Raine Turner, being reduced to just a name.

She fights Ruth as she drags her inside the diner and refuses to tell her where her car keys are. The weekend cook and the customer are gone already, the whole building empty and yawning. Kathleen’s screams bounce off the walls and ping around them. She’s scratching at Ruth’s arms, trying to kick and bite. She has to get to Raine. There’s nothing else for her but him and his fate.

And Kathleen will make Ruth bleed if she stops her.

“Kathleen, stop! What are you doing?!” Ruth’s arms are wrapped around Kathleen from behind, and Kathleen rams her body backwards towards a wall to get Ruth off. She can hear the storm picking up outside, feeling the heavy foundation of the building shake with anticipation, bracing itself. A clap of thunder booms right above them, stunning Kathleen and causing her to fall gently back into Ruth’s soft, open arms. Her heart beats to the rhythm of the wind abusing the diner.

“I have to go, Ruthie,” Her voice is hoarse and she doesn’t sound like herself anymore. “I have to go. He’s all alone.” Kathleen’s crying now, her shoulders shaking with the sheer force of her tears. Her face is crumpled and red, burning hot.

A scoff so unlike her rattles around in Ruth’s chest, and Kathleen feels it reverberate down her spine. “You’re doing all of this, fighting me, screaming, trying to run into a literal tornado because of Raine Turner. It’s always going to be him, isn’t it? He doesn’t even know you, Kathleen. He has no idea who you are.”

“I have to save him, Ruthie. Have to be with him.”

Ruth sighs, whispers, “Why him? It’s always been him. We were in middle school. We were kids, and you chose some irrelevant weather guy. I never understood. I never understood why it was him, and not me.”

Another clap of thunder. The glassware rattles, somewhere. A window shatters.

“It was never going to be you, Ruthie.”

Ruth’s disappointment is palpable, her anger filling the diner in seconds. She shoves Kathleen off and keeps shoving, tears streaking down her face. Kathleen stumbles over her feet and crashes into the counter, sending salt, pepper, and sugar shakers flying to the floor. She doesn’t have it in her to fight back anymore. Ruth keeps hitting and pushing and crying and screaming and Kathleen can feel all of it at the base of her spine. She no longer has it in her to bite. Her mouth empty when Ruth’s is filled with tears.

She imagines reaching forward and licking Ruth’s tears off her cheeks, swallowing them whole and letting them build a home inside her stomach. Wants to reach out and tangle shaking fingers into Ruth’s curls, maybe rip off the gold cross necklace laying delicate against her breastbone, take the metal between her teeth and bite down. Check for signs of her God before pulling Ruth to her and sanctifying ten years of sinful thinking.

“I think I hate you, most of the time.” It’s not what Kathleen expects to say, not what she wants or needs to say.

Ruth pauses, her hands gripping Kathleen’s uniform. “I think I hate you most of the time too, Kathy.”

More thunder. Kathleen can feel the ground vibrate in time with the storm, the feeling reverberating through the soles of her tan saddle shoes and shooting up her spine like electricity. Her fingers twitch.

“Let me go. It’s my choice. It’s what I want.”

“Please don’t.”

With the last of her conviction, Kathleen grips Ruth tight, her fingers digging into the soft wool of Ruth’s nicest church sweater and pulling her in close. Somewhere nearby, lightning strikes and burns the earth. The gold cross resting on Ruth’s chest flashing bright and present for just a second. For as long as Kathleen’s known Ruth, she’s had Jesus posted right above her tits, always watching. Watching her. And for almost as long as Kathleen’s known Ruth, she’s had Raine Turner to save her from the penance of judgment.

This close, she can see where Ruth’s innumerable freckles begin and end, can sync their breaths together, can take all of her into her own lungs and hold her there, trapped. Another bolt of lightning, another flash of gold foil. Somewhere, there’s a pop and suddenly the diner is quiet. Suddenly, Raine’s no longer screaming through a small wall mount TV’s tinny speakers. The power’s gone out, the diner is dark, and it’s finally just them. Just Ruthie and Kathy, breathing each other’s air.

Slowly, as if approaching a wounded wild animal, Kathleen untangles a hand from Ruth’s sweater and reaches up. Her hands aren’t shaking anymore, her fingers don’t have the faintest tremor. Ruth’s skin is soft and warm when Kathleen rests a single finger on her chin, traces it up up up to her cheek and rests her palm there gently, barely pressing her hand to the full skin there. Kathleen can feel her heartbeat like this. Can feel that Ruth’s stopped breathing. The building shakes.

They’re so close Kathleen barely has to lean forward, barely has to dip her head to reach Ruth’s trembling lips. She’s still crying, but then, she’s never been able to stop once she really gets started. A scarce pressure soothing a common burn. Ruth comes back to her body, from the brink of something too close to lose. It starts slow, and then Ruth has her hands wrapped around Kathleen, a hand tangled in Kathleen’s hair. Ruth is breathing again. A strangled sound dies in both of their throats.

Ruth tastes salty, her tears as holy water streaking down her face, her tears blessed and soluble, pouring into Kathleen’s mouth like rain. Just like that, Kathleen is the one that’s drowning. Kathleen is the one dissolving inside herself, a hand reaching up through her throat begging to be pulled out and set free. And she’s spent too long making sure her skin remained her own. She’s spent too long with her mouth full of prayer, full of Raine and the generous grey feathers he offered her all those years ago in exchange for her sanity, for her social capital. She’s spent too long like this to abandon it now.

Another clap of thunder. This time it’s loud enough to shake dishes loose and send them clattering to the ground, the delicate crowns of plates shattering on impact.

With the last of her conviction, Kathleen slaps Ruth’s hands away and pushes her back. Not hard, not angrily, not with any sort of violence— She just pushes. And Ruth trips. And Ruth falls. And Ruth’s head catches against the corner of the back counter. She’s lying crumpled on the floor, in a river of blood flowing steadily from her head. Her breathing stutters and, Kathleen thinks, stops. Her fingers twitch.

They were born gods of want, reaching towards something unnamable. Ruth is limp. Her arms stretch out away from her body. Everything is loud. Everything is quiet. Everything is cold. Everything is hot.

Kathleen isn’t in her body anymore. She watches it take a step forward, towards Ruth, who’s by the window. The sun is partially in her eyes. The sun? Her body bends at the knees. Her body leans forward. Her body presses cracked lips against a temple slick with blood, burning. The only part of her that touches Ruth. There’s a metallic taste somewhere near her. The blood won’t stop coming.

Kathleen thinks only one thing as she grabs her car keys and her jacket: if severe-weather photographers existed during the time of Noah’s Ark, they would have been filthy rich. Storms have a smell. Fried ozone, diatomaceous earth, and damp animal shit. They’ve probably always smelled like this. God set a dangerous precedent when he enlisted Noah, drafted him in a climate war he had no business plowing through.

Everything has stopped. There’s no more rain. No more wind. No thunder or lightning. Kathleen’s ears ring and Ruth’s body shivers. Her saddle shoes clack against the linoleum as she makes her way to the front door, flipping the ‘open’ sign to ‘closed’ as she pushes her way through the door and steps out into blinding sunlight.

She doesn’t lock up behind her.

People who work at the diner aren’t supposed to park out front, those spaces are reserved for customers and health inspectors. The kind of people that pay and the kind of people that have the power to take away the money. Today, however, Kathleen’s 2001 Honda Civic is right next to the front door. She hadn’t felt like running across the parking lot in the rain at five in the morning.

Avoiding the massive puddle drowning her front tires, Kathleen opens the car door and pools in, putting the key in the ignition and turning. A slow pop song blares through tinny speakers. The tan saddle shoes are slick with blood, slipping off the gas pedal three times before she finally finds purchase and peels out of the parking lot, pressing down on the gas until the speedometer needle spikes to sixty.

The song surrounds her on all sides, boxes her in and melts into her ears. She matches her breathing with the beats, can feel snot running down her face as tears threaten her fabricated atmosphere. Lyrics write onto her bones words like, I’m sorry and waking up and coming back.

Tears aren’t things Kathleen’s ever been familiar with. She’s spent her life making it up as she went, never had time to maintain such an intimacy with herself. An allowance can’t be given when you were born where no one lives; a body like Kathleen’s wasn’t meant for stitches. Her resolve is built for her and her alone.

She gets to Parrish’s cornfield in thirty minutes. Just in time to watch the ropy strings of a tornado, it’s spinal column visible every time the epicenter shifts, touch the top of the crops and threaten the existence of everything solid.

Raine is there. Kathleen can see him now as she gets out of her car, which is still in drive and inching slowly forward. He stands in front of the cornfield, is still talking into a camera that now lacks a cameraman, who has started running and screaming towards the news van. He’s haloed by the approaching tornado— an angel waiting for judgment. Kathleen can see herself reflected in the viewfinder.

Kathleen thinks how much more she could be if she loved something that much, so completely. The thought tastes like salt in her mouth.

Beautiful work! The detailing is amazing 🤩

I've read this twice to fully absorb all the insane dynamics happening